Avian influenza viruses are heat-resistant and pose a serious threat to humans

A research team from the University of Cambridge and the University of Glasgow has announced that they have identified a gene that determines the temperature sensitivity of influenza viruses. Because avian influenza viruses can grow at temperatures higher than those experienced by humans with a fever, and because viruses can exchange genes during co-infection, this discovery is expected to be useful in elucidating the causes of influenza pandemics.

Avian-origin influenza A viruses tolerate elevated pyrexic temperatures in mammals | Science

Bird flu viruses are resistant to fever, making them a major threat to humans | University of Cambridge

https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/bird-flu-viruses-are-resistant-to-fever-making-them-a-major-threat-to-humans

Bird flu viruses are resistant to fever, making them a major threat to humans

https://medicalxpress.com/news/2025-11-bird-flu-viruses-resistant-fever.html

In a paper published in the academic journal Science, the research team revealed that they had identified a gene that plays a key role in determining the virus's temperature sensitivity.

Influenza viruses are divided into types A, B, C, and D, with type A being the most common. Although influenza A viruses are generally referred to as such, there are many subtypes, and waterfowl generally carry one of the subtypes of influenza A in their intestines, but they do not develop symptoms even when infected. However, as they mutate, they can acquire the ability (pathogenicity) to develop 'highly pathogenic avian influenza,' which has a nearly 100% mortality rate in infected birds within 10 days at the latest. For this reason, there is no virus called the 'avian influenza virus,' and the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries defines it as 'all influenza A viruses that infect birds are collectively called avian influenza viruses.'

For those who want to know about avian influenza: Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries

https://www.maff.go.jp/j/syouan/douei/tori/know.html

It is known that influenza viruses circulating among humans multiply easily in the upper respiratory tract at approximately 33°C, but do not multiply easily in the lower respiratory tract at approximately 37°C. On the other hand, avian influenza viruses tend to multiply easily in the lower respiratory tract, and in the case of natural hosts such as ducks and gulls, there have been many confirmed cases of infection occurring in the intestines, which can reach temperatures of 40-42°C. Furthermore, previous research using cultured cells has already shown that avian influenza viruses are resistant to the body temperature of humans with a fever.

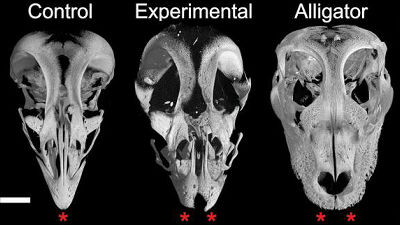

This time, the research team used influenza-infected mice to reproduce the fever response. Because mice do not normally develop fevers from human influenza A viruses, the research team raised the temperature of the mice's environment to raise their body temperature and mimic the fever effect of the virus.

The results confirmed that fever is effective in inhibiting the proliferation of common influenza viruses, and also revealed that a gene called 'PB1,' which plays a key role in replicating the viral genome within infected cells, holds the key to the virus's temperature sensitivity.

'However, the avian influenza virus was able to withstand the high temperatures caused by fever, causing the mice to become seriously ill. This discovery is important because, for example, if a human influenza virus and an avian influenza virus infect pigs at the same time, they may exchange genes within the host,' the research team said.

'The ability of viruses to exchange genes represents a continuing threat to new influenza viruses,' said lead author Dr Matt Turnbull of the University of Glasgow's Centre for Virus Research. 'In the 1957 and 1968 pandemics, we have seen instances of human viruses exchanging PB1 genes with avian influenza strains. This phenomenon may help explain why those pandemics were so severe.'

'Fortunately, humans are not particularly susceptible to avian influenza, but there are still dozens of cases each year,' said corresponding author Professor Sam Wilson of the Cambridge Institute of Therapeutic Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the University of Cambridge. 'The case fatality rate for humans infected with avian influenza is worryingly high, exceeding 40% in the historic pandemic H5N1. Understanding what causes avian influenza viruses to cause severe illness in humans is crucial for pandemic preparedness and vigilance.'

While the findings of this study may have implications for influenza treatment, there is clinical evidence that treatment with fever-reducing drugs such as ibuprofen and aspirin is not necessarily beneficial and may even promote the growth of influenza A viruses. The researchers emphasized that further research is needed before considering changing treatment guidelines.

By the way, the avian influenza virus has also infected seals, likely via seabirds, and mass deaths have been reported.

Mass deaths of elephant seals in South America's Patagonia as bird flu spreads - Nikkei

https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOGN16DWC0W4A110C2000000/

Related Posts: