What are the 'tips to winning rock-paper-scissors' revealed through neuroscience experiments?

Rock-paper-scissors, a game played not only in Japan but around the world, is a game in which the winner is decided by the number of fingers used (rock, scissors, paper). A research team from Western Sydney University has reported the results of an investigation into the human decision-making process in rock-paper-scissors from a neuroscience perspective.

Neural decoding of competitive decision-making in Rock–Paper–Scissors | Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience | Oxford Academic

https://academic.oup.com/scan/article/20/1/nsaf101/8269262

Even in a simple game, our brains keep score – and those scores shape every choice we make

https://theconversation.com/even-in-a-simple-game-our-brains-keep-score-and-those-scores-shape-every-choice-we-make-267117

In a competitive game like rock-paper-scissors, the mathematically most advantageous strategy is 'complete randomness.' If your hand is unpredictable, your opponent will be unable to devise a counterstrategy, and the odds of winning will converge to a 50/50 chance. However, it is extremely difficult for humans to behave completely randomly, and it is known that we unconsciously develop patterns and biases.

To dig deeper into this phenomenon, a research team from the University of Western Sydney conducted an experiment in which 62 participants were paired up and played a total of 480 computerized games of rock-paper-scissors. The games were divided into a two-second 'decision phase,' a two-second 'answer selection phase,' and a one-second 'result display phase,' allowing for detailed analysis of the brain information at each stage.

This experiment used a technique called 'hyperscanning.' While most previous social neuroscience studies measured the brain activity of a single participant, hyperscanning simultaneously records the brain activity of two interacting people. This makes it possible to capture how the brain processes information in real time in social contexts such as cooperation and competition.

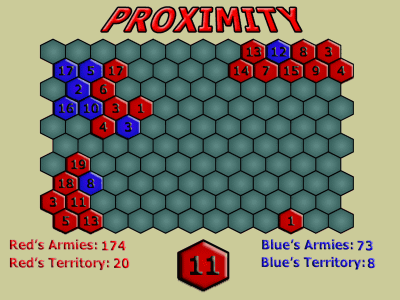

Analysis of the behavioral data obtained from the experiment revealed specific tendencies that prevent humans from being completely random. In theory, each of the three hands, Rock, Paper, and Scissors, should be selected 33.3% of the time. However, participants actually tended to over-select 'Rock,' with 51.61% of participants selecting 'Rock' as their most popular hand. Meanwhile, participants were least likely to prefer 'Paper, Scissors,' at just 14.52%. Furthermore, many participants tended to change their next hand regardless of the outcome of the previous game, indicating bias.

Furthermore, the research team applied an advanced analytical technique called 'multivariate pattern analysis' to the EEG data to attempt to decipher the player's thoughts from patterns of brain activity. As a result, they found that the brain's electrical signals could predict the next move even during the 'decision-making phase,' before the player presses the button to select their move. This indicates that the decision-making process is taking place in real time in the brain, before conscious action occurs.

Furthermore, when the brain activity of the 'winners' who ultimately won most of the games was compared with that of the 'losers' who lost, the brains of the losers were found to retain more information about their past decisions, such as what they had played in the previous game and what their opponents had played. On the other hand, no information about past history was detected in the brains of the winners.

The research team points out that these results offer important insights into the role of 'memory' in competitive situations. Generally, learning past information is advantageous for survival and cooperation, but in competitions where randomness is the optimal solution, such as rock-paper-scissors, being held back by past results can actually be disadvantageous. The loser unconsciously makes assumptions such as, 'My opponent played rock last time, so next time...' and as a result, their own behavior becomes patterned, making them more predictable to their opponent.

The human brain is not designed to generate completely random numbers, and has a tendency to constantly try to predict the future from past events. When building cooperative relationships, it is useful to predict the actions of others and make your own actions predictable, but in games like rock-paper-scissors, where complete randomness is most advantageous, this brain habit can be a disadvantage. The research team argued, 'The secret to winning at rock-paper-scissors may be to focus your thoughts on the present and forget the past, rather than over-analyzing past wins and losses or your opponent's moves.'

Related Posts: