AI-generated 'images that look different when rotated' are useful for perception research

Visually arresting materials are often used in psychology and neuroscience research. Researchers at Johns Hopkins University wondered whether optical illusions, which allow images to appear different when rotated, could be used in such research. They conducted an experiment using AI to generate such images.

Visual anagrams reveal high-level effects with 'identical' stimuli: Current Biology

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822(25)01102-9

Seeing double: Clever images open doors for brain research | Hub

https://hub.jhu.edu/2025/10/06/visual-anagrams/

Tal Boger of Johns Hopkins University and his colleagues used an AI tool to generate 'visual anagrams,' which are optical illusions. While 'anagrams' refer to words that become different words when the letters are rearranged, 'visual anagrams' refer to pictures that appear different when rotated.

The image generated by the tool looks like this:

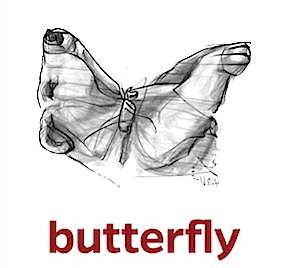

At first glance, the painting looks like a butterfly.

Rotate it 90 degrees to the right and it becomes a bear.

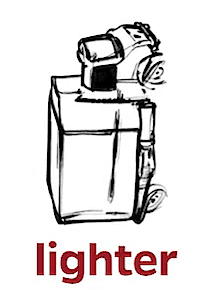

This is a picture of the writer.

Rotate it to turn it into a truck.

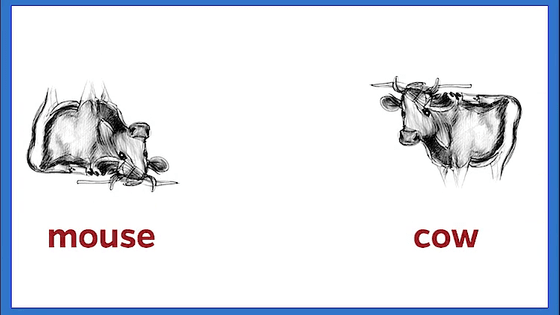

A picture of a mouse.

If you rotate it 180 degrees, it becomes a picture of a cow.

rabbit.

A rabbit becomes an elephant.

Duck facing left.

When I spun it, it turned into a horse.

Boger and his colleagues investigated whether these drawings could be applied to psychology and neuroscience, which explore how people perceive things in the real world.

In psychology, it is known that the brain automatically processes not only low-level stimulus properties such as brightness and contrast, but also high-level properties such as whether an object is alive, emotion, and real-world size. However, because low-level and high-level properties often strongly covary, it is unclear whether human perceptual processing is driven by high-level features or by low-level factors.

For example, when comparing an image of a large bear with an image of a small butterfly, not only are there differences in size but also in the complexity of their shapes, making it difficult to verify what actually triggers the brain's response.

So, Boger and his colleagues showed subjects 'visual anagrams' in which the same picture appears different when rotated, and investigated how the brain responds.

Boger and his colleagues first showed participants visual anagrams of the same size in two orientations, then asked them to resize them to the size they thought was ideal for the image. They found that when the image was oriented to look like a bear, participants adjusted the image size to be larger than when it looked like a butterfly.

This is in line with previous research showing that people perceive a picture with a size that matches its real-world size more favorably. The fact that subjects perceived the picture as having a different ideal size depending on how they viewed it, even though it was exactly the same picture, only viewed from a different direction, suggests that subjects were influenced by the higher-order characteristic of 'real-world size' during perceptual processing.

'These images can be used to study all kinds of effects, from size to animacy to emotion,' Boger and his colleagues wrote. 'We can study how people perceive pictures in ways that haven't been possible before. Not to mention they're fun to look at.'

Related Posts: