Musicians experience pain differently than the average person

Learning to play an instrument has been shown to have various benefits, not only in improving musical ability, but also in

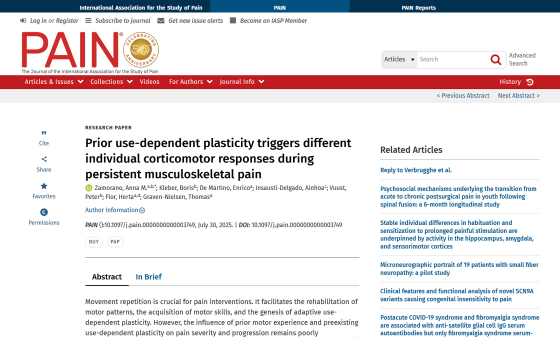

Prior use-dependent plasticity triggers different individual corticomotor responses during persistent musculoskeletal pain

https://journals.lww.com/pain/abstract/9900/prior_use_dependent_plasticity_triggers_different.981.aspx

Neuroscience finds musicians feel pain differently from the rest of us

https://theconversation.com/neuroscience-finds-musicians-feel-pain-differently-from-the-rest-of-us-265815

'Over the years of working with musicians, Zamorano has observed musicians repeatedly training to improve their playing skills, even in the face of pain from repetitive practice. This led him to wonder, 'If instrument training can change the brain in so many ways, could it also change how we perceive pain?''

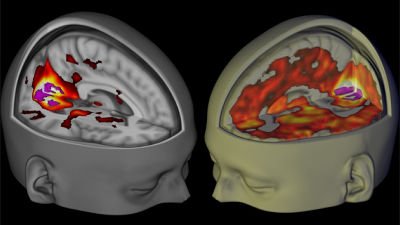

Previous studies have shown that pain alters various responses of the body and brain, reducing activity in the motor cortex, the area of the brain that controls muscles, and preventing overuse of an injured area, thereby helping to prevent further damage.

In this way, pain acts as a signal to protect the body in the short term, but if the pain persists and the brain continues to send the command 'stay still,' it can make things worse. For example, if you sprain your ankle and don't move it for several weeks, your ankle's mobility may decrease, inhibiting brain activity related to pain control.

Previous research has shown that persistent pain can shrink the 'body map,' the brain's 'brain' that sends instructions about which muscles to move and when, leading to more pain. While it's clear that some people experience more pain when their body map shrinks, not everyone is affected equally, and some people are better able to process pain.

Zamorano and his team investigated how instrumental training and the resulting changes in the brain affect how musicians perceive and cope with pain. They used

Nerve growth factor, a protein that helps keep nerves healthy, can cause pain for several days, especially when moving the hand. However, because the nerve growth factor has a safe and temporary effect, it does not cause any damage to the subject's muscles.

The researchers used transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a technique that delivers minute magnetic pulses to the brain, to create a body map of how the participants' brains control their hands. The TMS measurements were taken before, two days after, and eight days after the nerve growth factor injections to examine how pain affected the brain.

The results showed that even before pain was induced by nerve growth factor, musicians' brains had a more precise body map of their hands, and that this precision increased with longer practice. After pain induction, musicians reported less discomfort than the general population.

Furthermore, while the hand body map shrank in the brains of ordinary people even after just two days of pain, the hand body map did not change in the brains of musicians, and it was confirmed that the longer the practice time, the less pain they felt.

Although the experiment was small, involving only 40 people, the musicians' brains clearly responded differently to pain. The results of this study suggest that long-term musical instrument training may change how we perceive pain, which may help us understand why some people are more tolerant of pain and may lead to the development of new treatments.

'Musician training appears to have provided a kind of buffer against the usual adverse effects, both in terms of pain intensity and the response of the motor cortex of the brain,' Zamorano said. 'What's most exciting to me is the idea that the daily act of learning and practicing as a musician doesn't just improve technique, it has the power to literally rewire the brain and change the way we see the world. Even something as fundamental as pain can be transformed.'

Related Posts: