What would an engineer do if he realized that the Manhattan skyscraper he designed might collapse in a storm this year?

American structural engineer

The Most Dangerous Building in Manhattan - YouTube

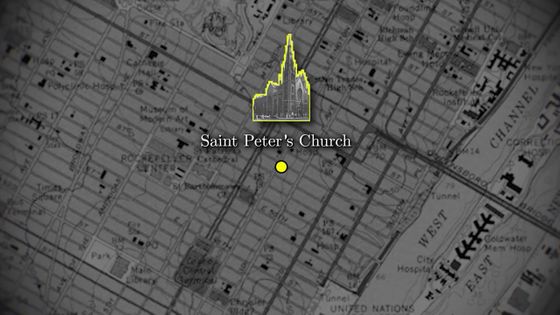

In the 1960s, the financial giant Citicorp (now Citigroup) was looking to build a new headquarters in Manhattan.

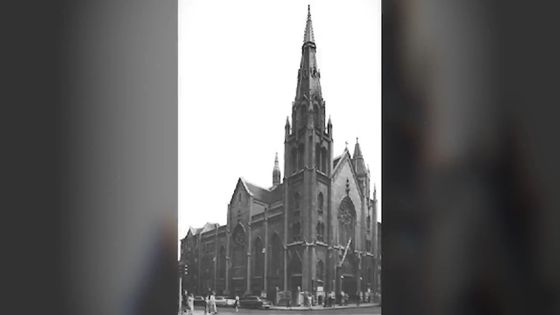

The entire neighborhood was up for sale, and on one corner of it was an old church called St. Peter's Evangelical Lutheran Church. Citicorp tried to negotiate, but the church refused to move.

In exchange, the church offered the condition that the old church be replaced with a new one and that it be separate from the Citicorp building.

So LeMahir was appointed as the design engineer for the new building.

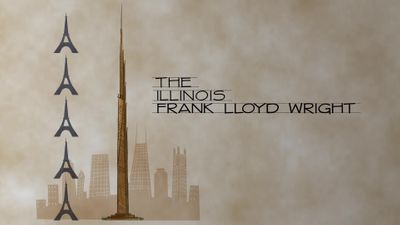

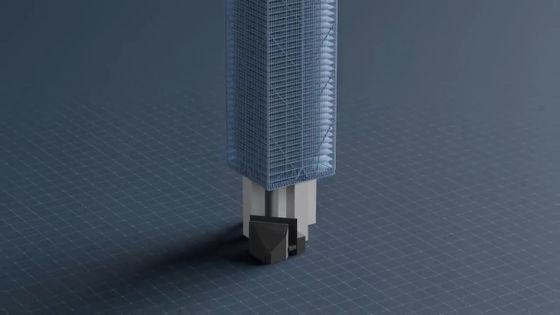

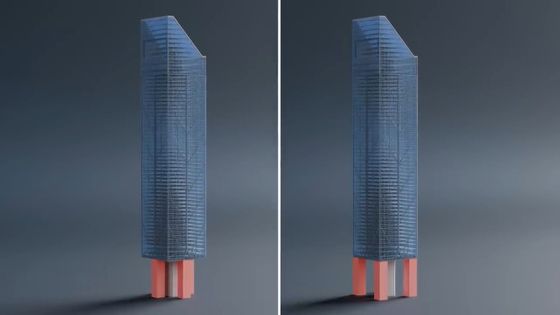

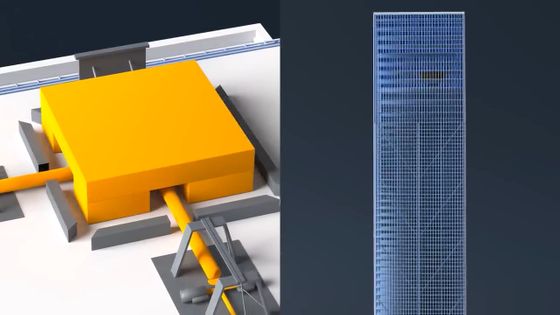

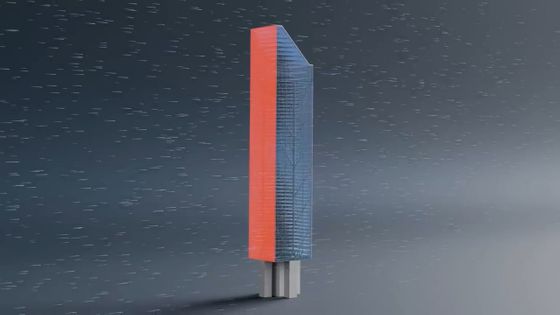

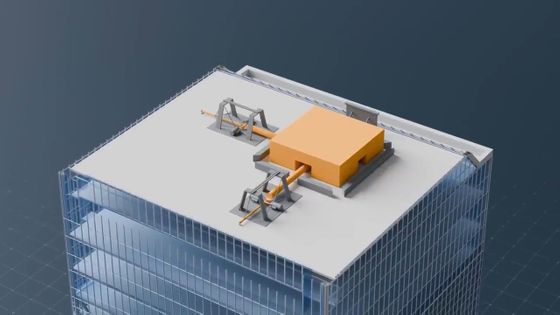

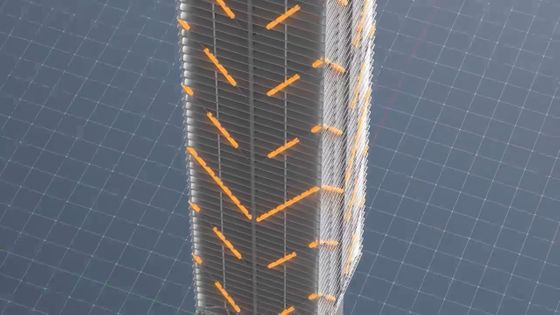

To maximize the floor space of the new building, a corner would have had to be carved out for the church, so LeMahieu came up with the idea of building a 'building on stilts,' removing all four corners.

This structure requires a central support to support the entire building as well as withstand strong wind loads, and is therefore less stable than a structure with four corner supports.

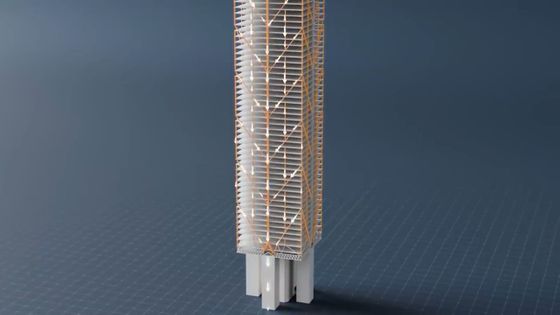

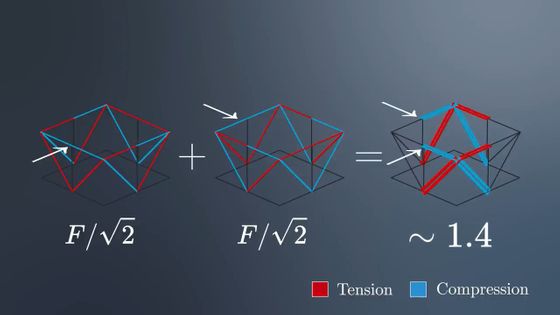

To solve this problem, LeMeasure proposed a six-story building with diagonal supports in a V shape, which would transfer the load to the central support.

LeMeasure removed the top and middle columns of the V-structure, allowing each level to function as an individual unit.

The strong winds that blow into high-rise buildings were also an issue during the design process, and the loads from these winds increase the lower you go, but the V-shaped structure solved this problem.

The pillars used in the V-shaped structure are each 40 meters long, so the parts were welded on site.

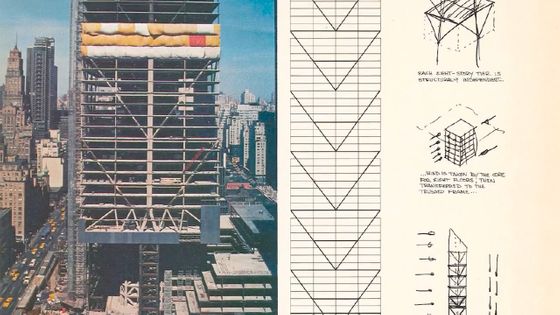

The Citycorp Center under construction looks like this. The V-shaped structure has significantly reduced costs and weight.

The building with the diagonal cut in the middle is the Citicorp Center. Its light weight made it more susceptible to swaying in the wind, but at most this caused some discomfort to occupants.

Looking up at the final completed building from below, you can see that there are no pillars at the four corners, and the whole structure is supported by the pillars near the center.

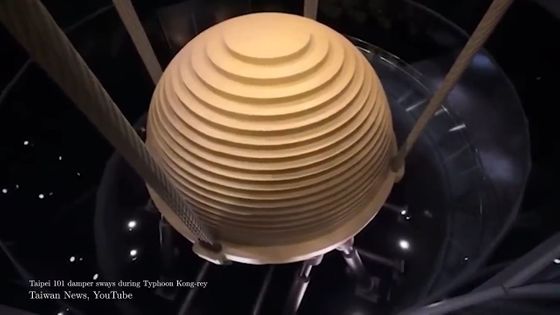

Additionally, to reduce the effects of wind on the Citicorp Center, LeMahir used a technology called

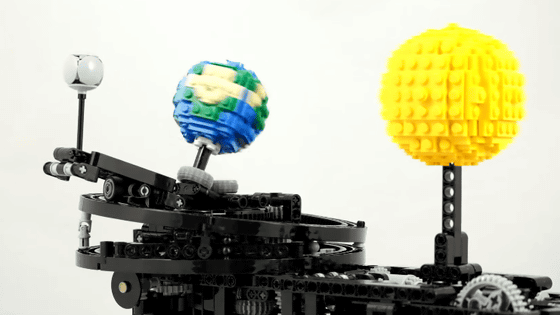

TMD is a device that uses a huge weight or pendulum as a mass to suppress the vibration of an object. A huge concrete block weighing 363 tons is installed as a mass on the top floor of the Citycorp Center.

When the Citicorp Center shakes, the concrete blocks begin to move in the same direction, dampening the vibrations of the entire building. LeMahieu said that by adopting TMD, 2,800 tons of steel would no longer be needed, resulting in significant cost savings.

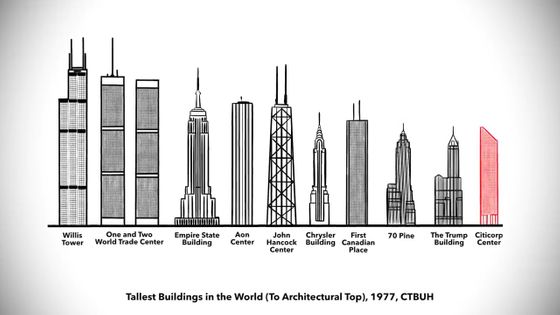

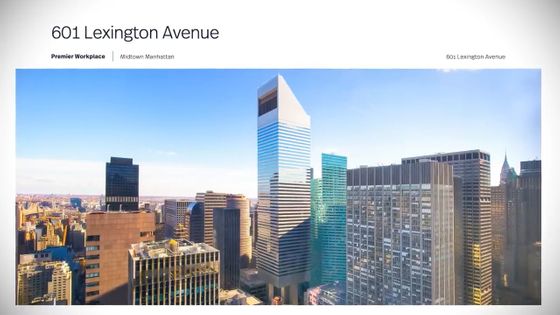

When it opened in 1977, the 279m-tall Citicorp Center was the 11th tallest building in the world and was acclaimed for its engineering and design.

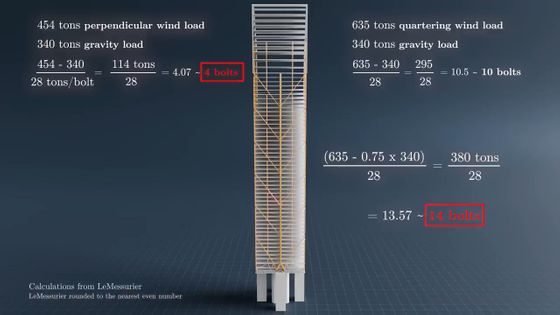

Shortly after the building opened, in May 1978, LeMajor called the New York office to inquire about the welding of the Citicorp Center after talking to another client about welding the V-shaped structures. It turned out that the contractor had bolted the V-shaped supports together to save on costs, when they should have been welded. Unbeknownst to LeMajor himself, his company had agreed to the change.

While bolts aren't necessarily worse than welds, they do change the forces placed on the V-structure, but LeMeasure believed the construction team had done the right calculations to make sure that bolting over welding would be okay.

But a month later, LeMahir got a call from a student who told him that a professor had concerns about the design of the Citicorp Center.

'Your professor is exaggerating. He doesn't understand the problem we had to solve,' LeMahieu later recalled telling his students. LeMahieu then worked with his students to recalculate the design and make sure it was correct.

However, around this time, LeMahir began to wonder, 'What would happen if the wind blew at an angle rather than from the front of the building?'

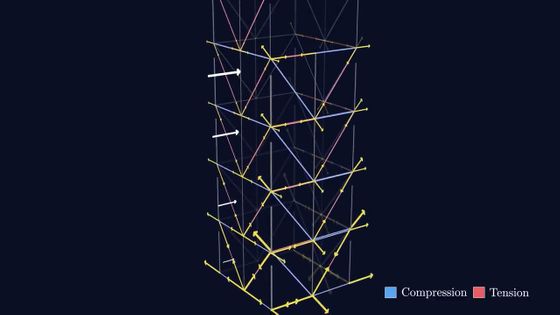

After recalculating, he found that the wind blowing at an angle increased the stress on certain beams by 40 percent, and LeMahieu became concerned because the V-shaped supports were bolted rather than welded.

In his office, LeMahieu scoured the building's drawings to see how the firm's team had calculated the wind, and found that they had not taken into account diagonal winds.

After detailed examination, it was discovered that only four bolts were used in an area where 14 bolts were actually required.

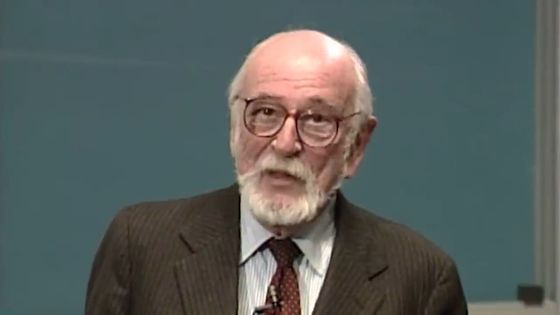

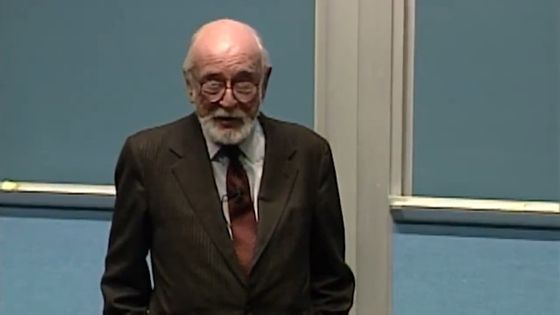

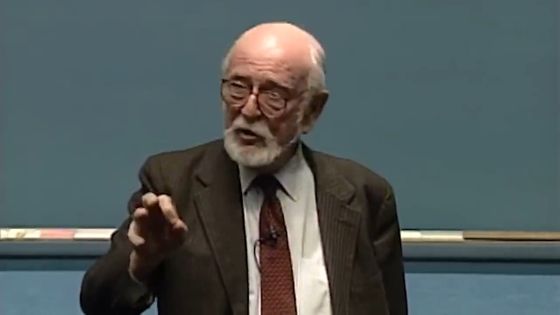

'You can imagine what LeMahir was thinking at that moment,' Hines said. 'He looked at the numbers and he was thinking, 'Oh my goodness. This is really bad.''

LeMahieu suppressed the urge to panic and went to

LeMeasure reviewed this data and determined that the weakest joint was on the 30th floor of the building: if this joint failed, the entire Citicorp Center would collapse.

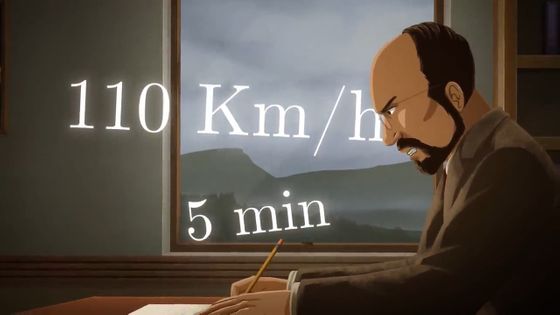

In addition, a thorough study of past weather forecasts revealed that winds strong enough to collapse the Citicorp Center occurred once every 67 years. It was also found that if the TMD failed due to a power outage caused by a storm, the Citicorp Center would collapse if winds blew at 110 km/h for just five minutes. The probability of a storm of the same magnitude occurring in a year was a whopping 1 in 16, and winds of 110 km/h also blew when

When asked, 'How do you think LeMahir felt when he performed this calculation?' Hines replied, 'It must have been devastating. I can't imagine the fear or the feelings.'

'A storm like that would have happened in my lifetime,' LeMahieu recalled. 'By the time I realized this, it was July, and it could have even happened that summer.'

LeMeasurer had to make a decision: reporting a serious construction error could have resulted in costly lawsuits and bankruptcy -- his own downfall. He could turn a blind eye, pray for a miracle that no major storms would occur, or disappear.

In a later interview, LeMahieu said he even considered committing suicide by driving his car into a bridge pier.

However, LeMajor decided to tell the truth and take action to save millions of lives. He spoke to lawyers and engineering experts, and notified

Within a few hours of the meeting, an emergency generator was procured to keep the TMD running even in the event of a power outage, which temporarily prevented any increased risk of collapse due to a power outage.

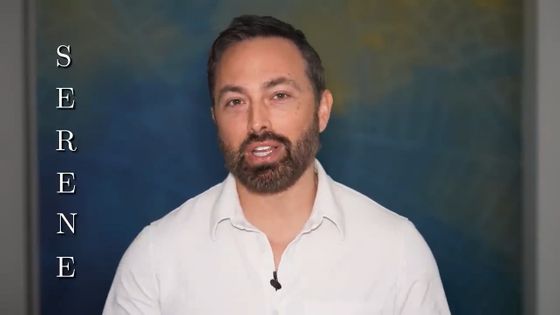

LeMahir and his team launched 'Project Serene,' an acronym for 'Special Engineering Review Events Nobody Envisioned.'

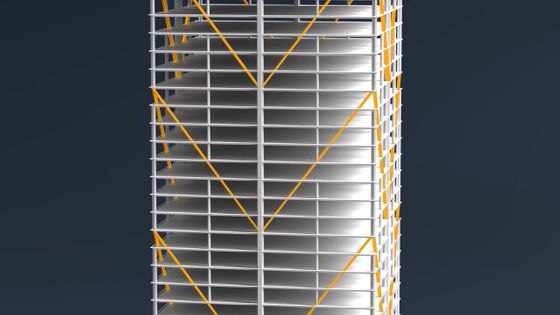

At Project Serene, repair work involved 'welders coming in every night after the Citicorp Center employees had gone home, removing the plasterboard around the V-structure and welding two 5cm-thick, 2m-long steel plates to each joint.'

Then, in the morning, they replaced the wall and put everything back together before the employees arrived at work.

In total, more than 200 joints needed to be welded, and LeMahir ranked them in order of importance, starting with the 30th floor, which was the weakest.

However, since it was impossible to complete all the repairs before hurricane season, Citicorp also worked with the Red Cross to develop an evacuation plan for the surrounding area.

In the worst case scenario, the Citicorp Center could have collapsed and hit other buildings, creating a domino effect.

Project Selene was carried out in secrecy, as they did not want to cause a major panic. Instead, they installed strain gauges on key structural components to send warnings if there were any problems. This would have required months of telephone line construction, but Liston called the president of AT&T and had it done overnight.

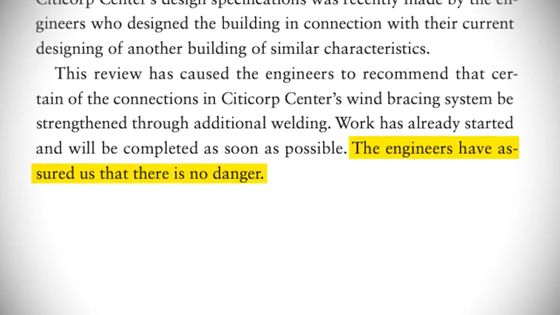

Project Selene was being carried out in secrecy, but as people around the company began to have doubts, Citicorp released a statement about the repairs on August 8. This time, they were forced to lie and say that their engineers had assured them that there was no danger.

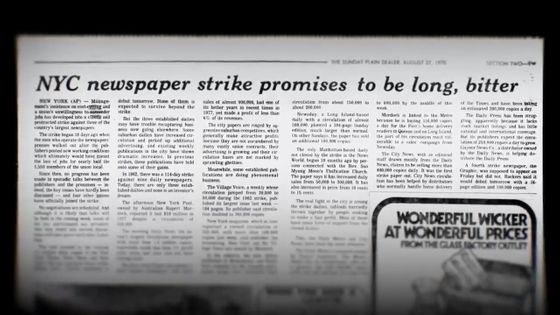

Several newspapers ran reports about the case, and eventually even the major daily newspaper, The New York Times, contacted him. Fearing that if he didn't respond to their inquiries, the New York Times would uncover the whole story, LeMahieu decided to make the call himself.

However, the New York Times did not answer Mr. LeMahieu's phone call, and instead played a voice on a tape recorder reporting that 'The New York Times has gone on strike.' Instead, newspapers across New York simultaneously began a strike until October, and the crisis of Project Selene being exposed was averted.

'It was the most amazing thing that's ever happened to me,' LeMahieu said.

Work on the ship continued smoothly until late August, when

Hurricane Ella was heading toward New York with winds of up to 200 km per hour. On September 1, just before landfall, police were preparing to visit residents within a 10-block radius and evacuate them one by one.

However, after spending nearly 24 hours off the coast of North Carolina, Hurricane Ella changed course and headed toward Canada with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph.

The change in course saved the Citicorp Center, and LeMahieu described the morning after Hurricane Ella passed as 'the most beautiful day in the world.'

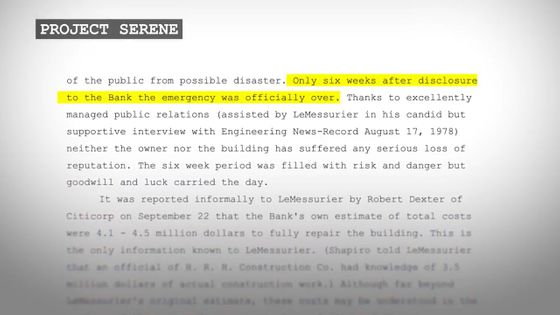

The repairs were completed in October, just six weeks after LeMahieu discovered the problem. The repairs were costly, but Citicorp paid generously, thanks in part to cost savings from the original design.

Project Selene remained secret for nearly two decades, until a 1995 weekly magazine, The New Yorker, broke the story. Rather than being criticized, LeMahieu was praised for admitting his mistake and quickly resolving the problem.

After this article was published, New York City amended its building codes to require that designs take into account diagonal winds as well as frontal winds.

In addition, TMD, which was first introduced at the Citicorp Center, is now used in high-rise buildings around the world, especially in Japan.

Six of the 20 tallest buildings in the world have TMDs installed, and

There are various theories about who the student who called LeMahir was. One theory is that it was Diane Hartley, a structural engineering student at Princeton University. Another man, Lee DeCarolis, a student at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, also said he had spoken to LeMahir.

The Citicorp Center was subsequently sold in 2001 and is now known as 601 Lexington Avenue.

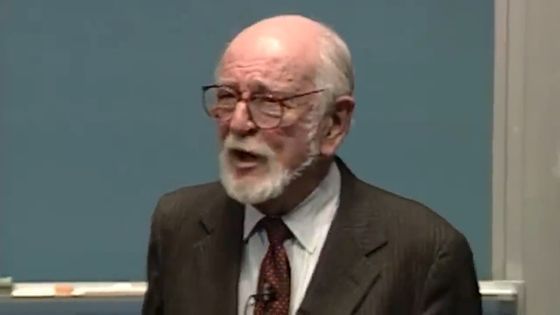

In the engineering community, LeMahieu's actions regarding the Citicorp Center are considered honorable and ethical, and are taught in college courses as an example of good engineering ethics.

Related Posts:

in Video, Posted by log1h_ik