Scientists prove the existence of a 'second stomach' that can hold dessert

Many people have had the experience of being so full that they can't eat any more, but then when dessert is presented to them, they gobble it down in one go. In an experiment in which mice were given additional dessert after eating a full meal, it was discovered that there is a 'dessert stomach' area in the brain that releases pleasure-inducing substances only when they eat something sweet when full. Since a similar mechanism exists in the human brain, the researchers hope that this discovery could lead to the development of drugs and treatments to prevent overeating and obesity.

Thalamic opioids from POMC satiety neurons switch on sugar appetite | Science

'Dessert stomach' finally found in the brain

https://newatlas.com/biology/dessert-stomach-brain-sugar/

So THAT's why you always have room for pudding! Scientists prove 'dessert stomach' is real | Daily Mail Online

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-14394303/Scientists-prove-dessert-stomach-real.html

Why we may crave dessert even when we are full from dinner | New Scientist

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2468346-why-we-may-crave-dessert-even-when-we-are-full-from-dinner/

In a paper published in the scientific journal Science on February 13, 2025, a research team led by Henning Fenselau of the Max Planck Institute for Metabolism reported the results of a study examining the response of mice to foods high in sugar.

In this experiment, mice were first given pellets containing only 3% carbohydrate and were allowed to eat for over 90 minutes until they were full. Once full, the mice were given either regular pellets or additional sweet and tasty pellets containing 35% carbohydrate, and the eating behavior of the mice was observed during the 30-minute dessert period.

The results showed that the mice fed the high-sugar pellets consumed six times as many calories as the mice fed the normal pellets, confirming that mice also have a separate stomach for sweets.

'From an evolutionary perspective, this makes sense: sugar gives us quick energy, but it's scarce in nature, so our brains are programmed to control our intake of sugar whenever it's available,' said Fencelau, corresponding author of the study.

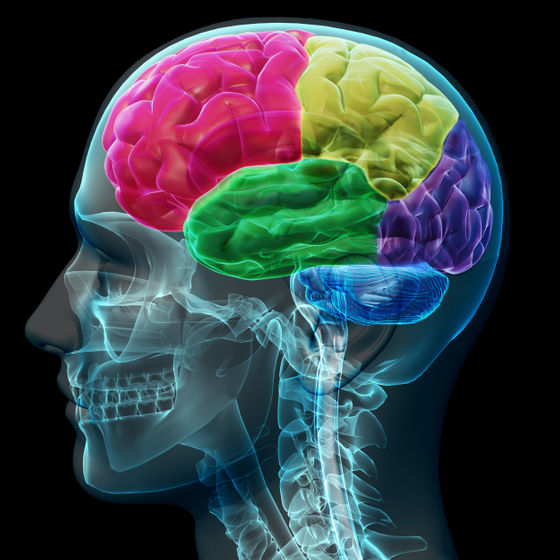

Furthermore, when the research team examined the brains of mice that were given sweet desserts, they found that

POMC neurons are generally activated after a meal to prevent overeating, but when mice saw dessert after a meal, POMC neurons sent satiety signals to the adjacent thalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVT), causing the release of endorphins, which are pleasure-inducing chemicals.

The research team calls this brain region the 'separate abdominal region,' and the mechanism that causes the mice to eat more sweets than they can by releasing pleasure-inducing substances is called the 'opioid pathway.'

The opioid pathways in the brain were activated when the mice ate sweet foods, but not when they ate regular or fatty foods, and when the researchers blocked the opioid pathways in the mice, they found that full mice stopped eating more sugar, but interestingly, this had no effect on suppressing endorphin release in hungry mice.

'These types of cells, which are well known for making us feel full, also release signals that trigger sugar cravings, especially when we're full,' Fenselau said. 'This could explain why people eat too much sugar even when they're actually full.'

To test whether the same mechanism actually works in the human brain, the research team recruited 30 volunteers and had them drink a sugary drink while undergoing MRI scans.

They then confirmed that, like mice, humans also have a 'separate abdominal region' in the brain, and that opioid receptors exist near POMC neurons, suggesting that blocking this mechanism could be a new approach to suppress overeating and obesity.

In fact, when the researchers activated POMC neurons using a technique called optogenetics, which stimulates brain neurons with light signals, the mice consumed more cherry- or lemon-flavored pellets, even though they contained no sugar. This indicates that the mice felt like eating more. Conversely, blocking the signals sent from POMC neurons to the PVT reduced dessert intake by 40%.

'There are already drugs that block opioid receptors in the brain, but they don't result in as much weight loss as appetite-suppressing injections, so we think combining such drugs with appetite-suppressing injections and other treatments could be very effective, but more research is needed to be sure,' Fencelau said.

Related Posts: