Research results show that humans also have the ability to move their ears to concentrate on sound

Animals such as dogs and rabbits perk up or twitch their ears in response to sound. This movement focuses sound on the animal's eardrum, which is important for accurately identifying and processing the sound. Research conducted at the University of Saarland in Germany has found that humans also have the ability to move their ears in response to sound.

Vestigial auriculomotor activity indicates the direction of auditory attention in humans | eLife

'Vestigial' human ear-wiggling muscle actually flexes when we're straining to hear | Live Science

https://www.livescience.com/health/anatomy/vestigial-human-ear-wiggling-muscle-actually-flexes-when-were-straining-to-hear

Robert Wiederheim, a German anatomist active in the late 19th century, states in his book ' The Structure of Man ' that humans have 86 vestigial organs . Vestigial organs are organs that have degenerated and no longer serve their original purpose, but only retain their shape. Representative examples include the nipples in men, the coccyx (part of the tail), and wisdom teeth.

Not just 'men's nipples': 10 seemingly useless parts of the human body - GIGAZINE

The auricular muscles, which allow ear movement, are also a vestigial organ. Many animals can move their ears in response to sound, but humans have lost all or most of this function during evolution. Some people can move their ears intentionally, but this ratio is said to be about one in 1,000. The auricular muscles of modern humans are small and can only exert a weak force, but it was thought that the auricular muscles were still strongly developed in our distant ancestors, and that they helped improve hearing by moving the ears back and forth to capture sound more effectively.

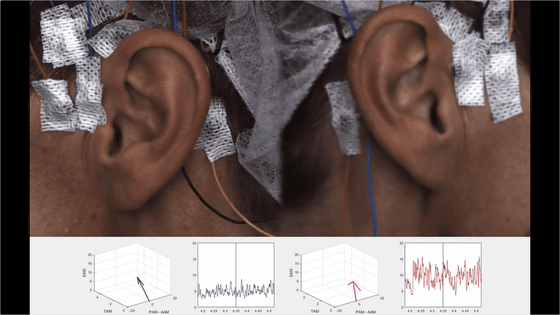

To learn more about the capabilities of the auricular muscles, the researchers attached electrodes to the scalps of 20 participants with normal hearing to track electrical activity in the superior and posterior auricular muscles, located above and behind the ear. The participants sat in a soundproof room with their heads held in place while listening to an audiobook playing in the room, along with a podcast playing for added distraction.

The experiment was repeated 12 times, dividing the difficulty level into low, medium, and high levels by adjusting the volume of the audiobook and podcast, and the position from which the sound was heard and the activity of the auricular muscles were recorded. As a result, it was found that the subjects' posterior auricular muscles were more active when the sound of the audiobook they wanted to listen to came from behind them than when the sound came from the front. In addition, although the superior auricular muscles were not affected by the direction of the sound, they became more active as the listening level increased. The researchers suggest that 'the posterior auricular muscles are thought to be vestigial organs that helped our ancestors detect sounds from outside their field of vision. The superior auricular muscles are also correlated with how much effort a person makes to listen consciously.'

On the other hand, Matthew Winn, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, points out that 'We cannot conclude from this study that the auricular muscles are active to pick up sound, because the response of the auricular muscles may reflect a state of heightened vigilance against sound or frustration with noise.' In addition, according to Steven Hackley of the University of Missouri, co-author of the paper, even if the ear movements observed in the study were an attempt to hear sound, they were too small to affect hearing. However, he hopes that these findings could be applied to practical uses such as assisting hearing aids.

Related Posts:

in Science, Posted by log1e_dh